The news that the Farmers' Almanac is ceasing publication after 208 years has, predictably, sparked a wave of nostalgia. Social media is awash with digital tears, as evidenced by the 3,000 "shocked or sad reactions" on the Illinois Storm Community Facebook group. But let's be clear: This isn't exactly the end of an era, at least not in the way people seem to think.

The confusion stems from a simple fact: there are two almanacs. The one shutting down is the Farmers' Almanac, based in Lewiston, Maine, and owned by the Geiger family. The other one, the Old Farmer's Almanac (note the "Old"), based in New Hampshire and owned by Yankee Publishing, is alive and well. (Their Christmas forecast, I might add, was released this week.)

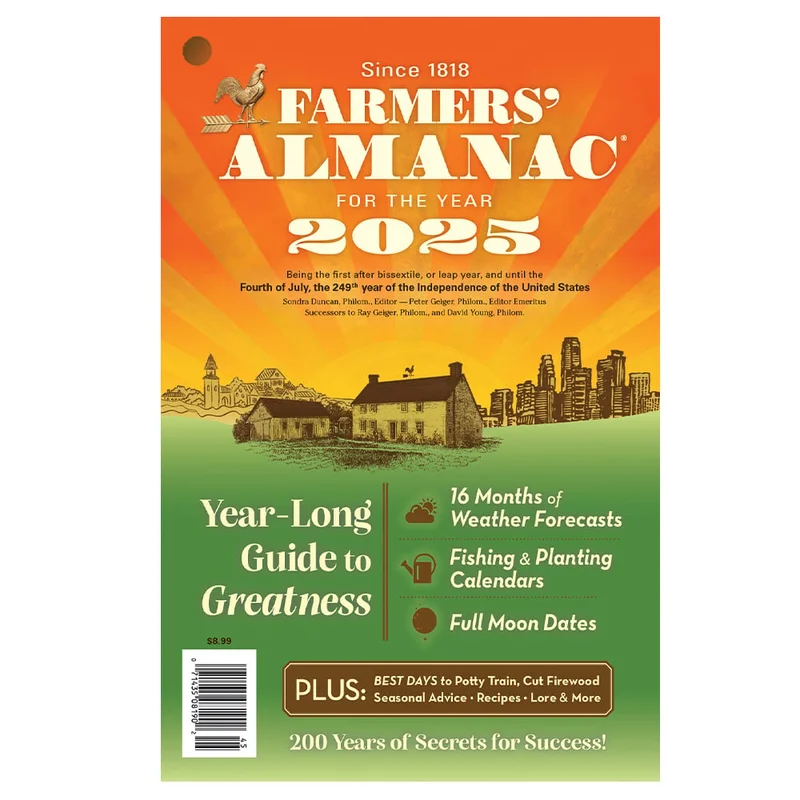

The media's initial coverage didn't exactly help. Several outlets, iHeartRadio included, ran stories about the "Farmers' Almanac" closing, illustrated with photos of the Old Farmer's Almanac. This created a false impression that the more widely recognized (and, let's be honest, cuter, with its yellow cover) almanac was the one on its deathbed. The cute yellow Old Farmer’s Almanac isn’t the one shutting down

David Geiger, the fifth-generation owner of the Farmers' Almanac, cited declining newsstand sales as the primary reason for the closure. "Readers now access information and answers differently," he told the Sun Journal. Which is a polite way of saying that in the age of hyper-local weather apps and instant Google searches, a yearly almanac is about as relevant as a rotary phone.

But here's where things get interesting. Geiger states that the Farmers' Almanac "represents a small part of our overall business." This raises a key question: what exactly is the "overall business"? Details on the Geiger family's other ventures are scarce, but the Almanac's revenue stream, or lack thereof, clearly wasn't enough to justify continued publication. Was the Almanac subsidized by a larger, more profitable enterprise? And if so, why did that subsidy end now?

Sandi Duncan, the Farmers' Almanac's editor, stated that the publication's "spirit will live on in the values it championed: simplicity, sustainability, and connection to nature." It's a nice sentiment, but let's unpack it. "Simplicity" in the age of complex algorithms? "Sustainability" in a world grappling with climate change data far beyond gardening tips? "Connection to nature" when most people get their nature fix through Instagram?

The Almanac's brand was built on a romanticized vision of rural life, but the reality is that farming has become increasingly industrialized and data-driven. Modern farmers rely on sophisticated weather models, soil analysis, and precision agriculture techniques. A 200-year-old almanac, however charming, simply can't compete with that level of granular data.

The Facebook group Illinois Storm Community, with its 411,000+ members, is a fascinating example. While the initial reaction to the news was overwhelmingly negative, a closer look reveals a more nuanced picture. Commenters quickly clarified the confusion between the two almanacs, with many emphasizing that it was not the "OLD farmer's almanac with the yellow cover" that was shutting down. This suggests that the brand of the Old Farmer's Almanac holds significantly more cultural cachet than the actual information it provides.

The question isn't just why the Farmers' Almanac is closing, but why the Old Farmer's Almanac continues to thrive. Is it superior forecasting? (Unlikely, given the inherent limitations of long-range weather predictions.) Is it better gardening advice? (Perhaps, but the internet is flooded with such content.) Or is it simply a matter of branding and nostalgia?

Ultimately, the demise of the Farmers' Almanac is a case study in market forces. The publication failed to adapt to the changing information landscape, and its revenue model proved unsustainable. While the sentimental value of a printed almanac is undeniable, the cold, hard data tells a different story. The "chaotic media environment," as the Farmers' Almanac release called it, simply doesn't have room for two competing, nearly identical, and increasingly obsolete publications. The Old Farmer's Almanac still stands, for now, but it too may be facing an uphill battle. The future belongs to those who can deliver precise, personalized information in real-time. An annual magazine, however charming, simply can't compete.